Cool Timeline

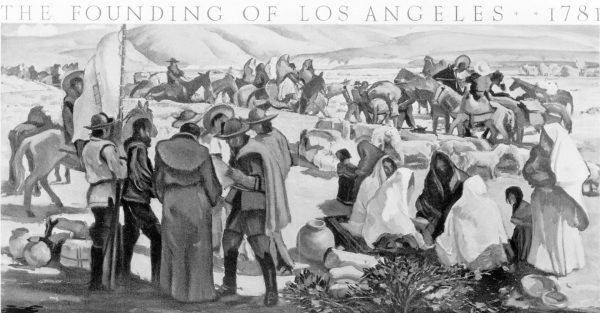

In 1781 11 Mexican families, totaling 44 settlers, led by Felipe de Neve the Governor of Spanish California, settled by the river. Neve names the settlement El Pueblo Sobre el Rio de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles del Río de Porciúncula. The 11 families were of European, African, and Native American backgrounds and they traveled from northern Mexico to help establish a farming village.

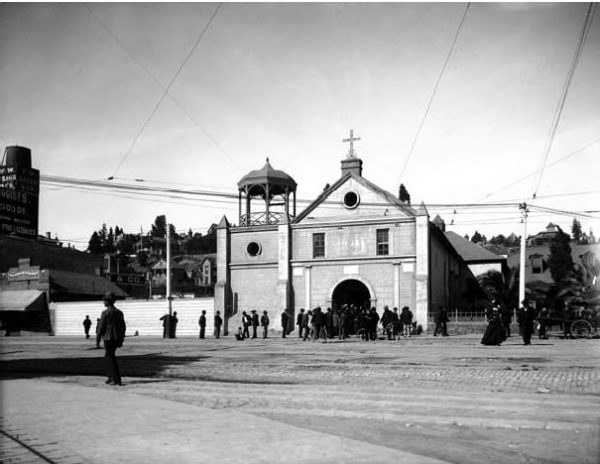

On August 18th, 1814 Father Luis Gíl y Taboada placed the cornerstone of a new Franciscan church amidst the ruins of the original asistencia.

The completed structure was dedicated on December 8th, 1822. This becomes the first Catholic church of Los Angeles.

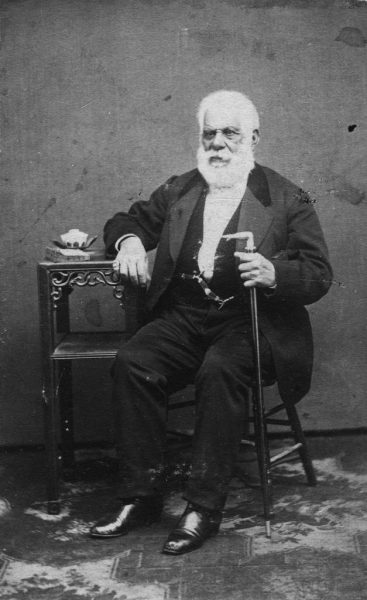

In 1844 he was chosen as a leader of the California Assembly.

In 1845, he was again appointed governor, succeeding Manuel Micheltorena. Pico made Los Angeles the province’s capital.

In the year leading up to the Mexican–American War, Governor Pico was outspoken in favor of California’s becoming a British Protectorate rather than a U.S. territory.

In 1846, when U.S. troops occupied Los Angeles and San Diego during the Mexican–American War, Pico fled to Baja California, Mexico, to argue before the Mexican Congress for sending troops to defend Alta California. Pico did not return to Los Angeles until after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and he reluctantly accepted the transfer of sovereignty.

In 1868, he constructed the three-story, 33-room hotel, Pico House, which was then most lavish hotel south of San Francisco and LA’s first three-story building.

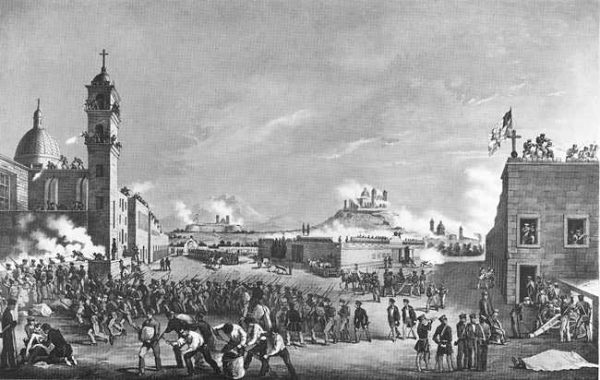

On June 18, 1846, a small group of Yankees raised the California Bear Flag and declared independence from Mexico in the Bear Flag Revolt in Northern California. United States troops then took control of the presidios at Monterey and San Francisco and proclaimed the invading “conquest” complete. In Southern California, the Mexican citizens repelled American troops for five months.

The small Mexican forces of Los Angeles fled at the approach of US troops, and on August 13, 1846, the American flag was raised over the city. Despite having opposed the Mexican invasion, the American occupation caused the remaining mixed populations to unite against the invading Americans.

Los Angeles was not retaken until Commodore Stockton again captured the city on January 10, 1847, after the battles at the Siege of Los Angeles, Battle of Dominguez Rancho, Battle of San Pasqual, Battle of Rio San Gabriel and the Battle of La Mesa.

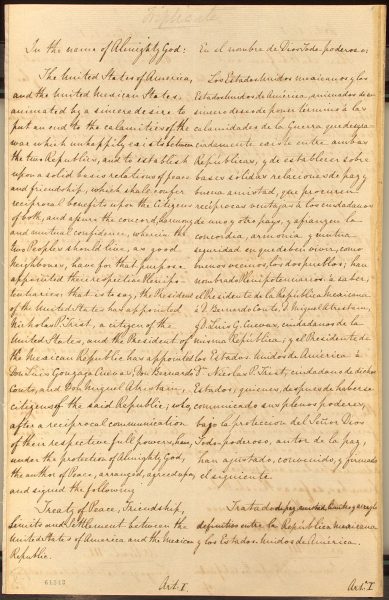

On February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed between the U.S. and Mexico.

The treaty called for the United States to pay $15 million USD to Mexico and to pay off the claims of American citizens against Mexico up to $5 million USD. It gave the United States the Rio Grande as a boundary for Texas. It also gave the U.S. ownership of California, and a large area comprising roughly half of New Mexico, most of Arizona, Nevada, and Utah and Colorado.

Mexicans in those annexed areas had the choice of relocating to within Mexico’s new boundaries or receiving American citizenship with full civil rights.

In 1848, the gold discovered in Coloma first brought thousands of miners from Sonora in northern Mexico on the way to the goldfields. So many of them settled in the area north of the Plaza that it came to be known as Sonoratown. The U.S. army swarmed in.

In 1848, California’s new military governor Bennett C. Riley ruled that land could not be sold that was not on a city map.

In 1849, Lieutenant Edward Ord surveyed Los Angeles to confirm and extend the streets of the city. His survey put the city into the real-estate business, creating its first real-estate boom and filling its treasury.

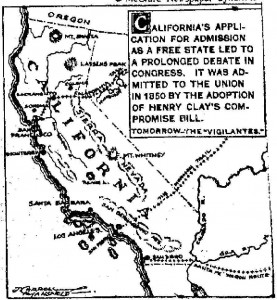

On April 4, 1850, Los Angeles was incorporated as a U.S. city. Five months later, California was admitted into the Union.

In 1865, Los Angeles’ first college was a private Catholic school called St. Vincent’s College, which served for both primary and secondary educations since there wasn’t a high school until 1873.

St. Vincent’s hosted classes at the Lugo Adobe house on the east side of the Plaza while a new building was being finished. The home was donated by Don Vicente Lugo, and it was one of few two-story adobes around. It used to be located on a lot across from Alameda Street between the Plaza and Union Station, (near Olvera Street).

After two years, the college and school moved into a new, brick building several blocks south by the lower plaza, Pershing Square.

Later, the brick building was replaced with a larger one made of stone that had a central tower with a dome located on the block of Broadway and Hill on 6th and 7th streets.

The 7th street property is now called St. Vincent’s Place.

In 1866 the city set aside 15 blocks for a city square. The ordinance, passed by the City Council and signed by Mayor Cristobal Aguilar, declared the tract “a public square or plaza for the use and benefit of the citizens in common of [Los Angeles].”

Block 15 remained a treeless town commons, known as Los Angeles Town Square because the ordinance had no funds for greenery or landscaping.

Livestock continued to graze on the land, and teamsters violated warning signs by driving their wagons through the public square.

In the 1860s, the Chinese population in Los Angeles was small but growing. This was thanks to the Southern Pacific Railroad hiring them for incredibly low paying railroad labor.

They settled in Olvera, specifically in a dirt alley known as Calle de Los Negros. It was one of the most dangerous places in America, at the time. Calle de Los Negros occupied a fairly small stretch of land 50 feet in width by 500 feet in length.

In March of 1855, The Los Angeles Star recorded 5 homicides in a 24 hour period.

In 1871, a tragedy descended on the Chinese people living there. A mob made up of 500 white Angelenos (one-tenth of the population at the time) marched into Chinatown to retaliate to the death of a white Rancher. That rancher died because he got caught in the crossfire of a Chinese gang war.

The angry mob asked no questions of gang relations and murdered 19 Chinese men and boys. This event came to be known as the Chinese Massacre.

In 1877, Calle de los Negros was renamed to Los Angeles Street.

The Chinese residents didn’t really have anywhere to go and by 1880, their population had grown from 234 to 1169. So they moved eastward of Los Angeles Street (Calle de Los Negros) to Alameda. They would later be moved again to make room for Union Station.

Biddy Mason (August 15, 1818 – January 15, 1891) was an African-American nurse and a Californian real estate entrepreneur and philanthropist.

After a turbulent time as a slave in the south, Mason got her freedom and moved to LA. She worked as a nurse and midwife, delivering hundreds of babies during her career. Using her knowledge of herbal remedies, she risked her life to care for those affected by the smallpox epidemic in Los Angeles.

Saving carefully, she was one of the first African American women to own land in Los Angeles. As a businesswoman, she amassed a relatively large fortune of nearly $300,000, which she shared generously with charities.

Mason also fed and sheltered the poor, and visited prisoners. She was instrumental in founding a traveler’s aid center, and a school and daycare center for black children, open to any child who had nowhere else to go. Because of her kind and giving spirit, many called her “Auntie Mason” or “Grandma Mason.

In 1872, along with her son-in-law Charles Owens, Biddy Mason was a founding member of First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles, marking it the city’s first black church.

The organizing meetings were held in her home on Spring Street. She donated the land on which the church was built.

On Sept. 22, 1873, public transit debuted in Los Angeles when Charles Dupuy opened his Pioneer Omnibus Street Line. The line’s horse-drawn vehicles, which resembled miniature railroad cars on large, wooden wheels, followed a regular schedule and a fixed route — a first in Los Angeles.

For nearly two years the Pioneer line’s buses moved riders between the historic Plaza located by today’s Olvera Street and Washington Gardens, a popular beer garden, and fairground located far south of the central city at Washington and Main.

But muddy streets pocked with holes plagued the line, which closed in 1875.

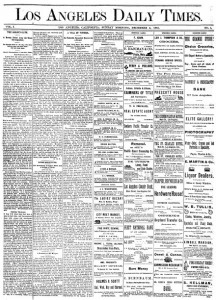

The Times was first published on December 4, 1881, as the Los Angeles Daily Times under the direction of Nathan Cole Jr. and Thomas Gardiner. However, they were unable to keep up with the financial demands of printing a newspaper.

In July 1882, Harrison Gray Otis moved from Santa Barbara to become the paper’s editor. Despite turning the paper into a conservative one, Otis made the Times a financial success.

Otis constantly insulted local unions, and they retaliated. Two union leaders, James, and Joseph McNamara, led a group of railroad union workers in the bombing of the Times headquarters on October 1, 1910, killing twenty-one people.

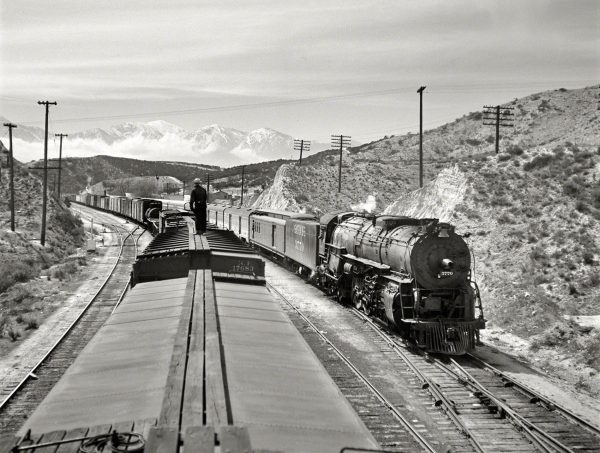

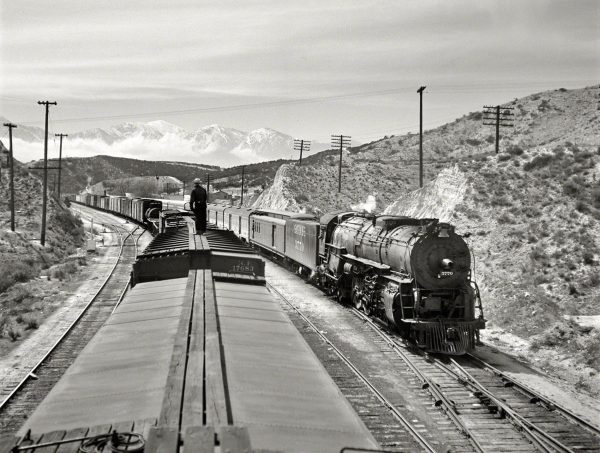

In 1885, the Santa Fe Railway gave Los Angeles its own direct line to the Eastern U.S. The line was in direct competition with the Southern Pacific.

Santa Fe’s entry into Southern California brought forth an economic growth, but it also ignited a ticket fare rate war with the Southern Pacific. It also led to Los Angeles’ well-documented real estate “Boom of the Eighties.”

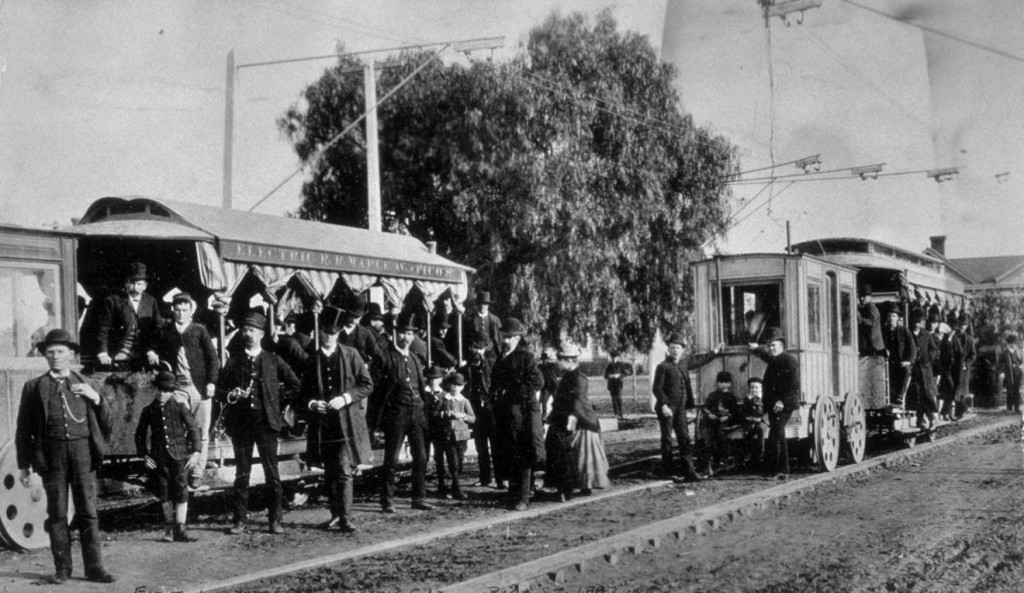

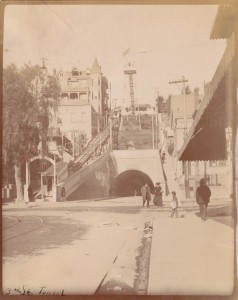

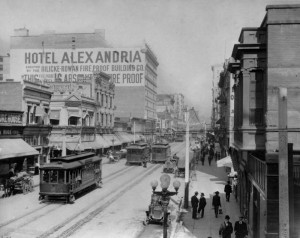

In 1887, the first electric streetcar appeared on a stretch of Pico Street to Downtown’s new booming Historic Core.

A historian for the website usp100la writes: “By 1911, Southern Pacific consolidated the entire electric interurban streetcar network of Los Angeles and operated it as the Pacific Electric Railway Company, whose cars were known as ‘Red Cars. Around the same time, the Los Angeles Railway operated a local system of streetcars in central Los Angeles, known as the Yellow Cars.”

However, the efficiency of the streetcars enabled people to move out of Downtown Los Angeles and on to the suburbs.

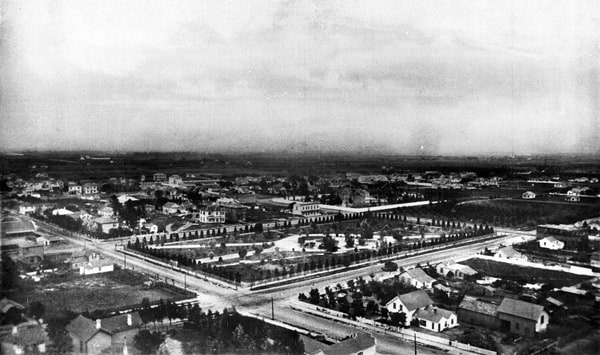

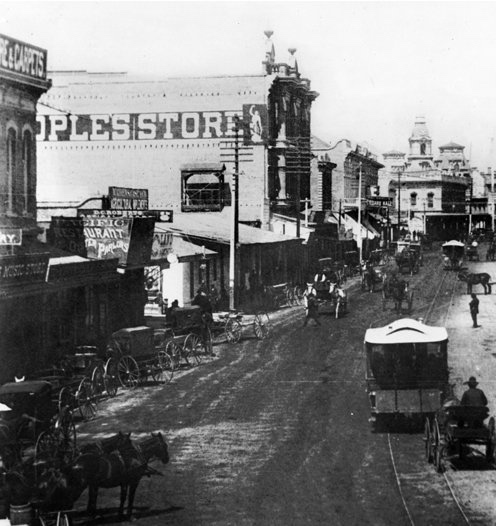

Thanks to the newfound mobility of streetcars and railroads the population in Los Angeles exploded during the 1880s and 1890s. The central business district (CBD) grew along Main and Spring streets towards Second Street and beyond.

This area would later come to be known as the Historic Core.

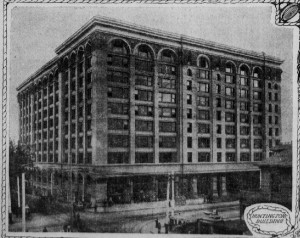

Lewis Bradbury was a gold-mining tycoon who made a fortune in Sinaloa, Mexico in the 1890s. In 1892, he became a real estate developer with his sites set on Downtown LA.

He began planning to construct his dream- a five-story building that would be located on Broadway and Third Street. Bradbury hired a local architect, Sumner Hunt, but Bradbury was ultimately displeased at Hunt’s “inadequate” design. One of Hunt’s draftsmen, George Wyman, did better in Bradbury’s eyes and he was hired to do the design.

The designs weren’t inherently different so this issue has raised some controversy about who should be considered to be the architect of the building.

The building opened in 1893 and was completed in 1894, but Bradbury didn’t get to see it because he died in 1892. It cost him a total cost of $500,000, which was about three times the original budget of $175,000.

In 1971, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places and in 1977 was designated a National Historic Landmark. It is one of only four office buildings in Los Angeles to be so honored. It was also designated a landmark by the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission and is the city’s oldest landmarked building.

The Rosslyn Hotel is built for the staggering sum of one million dollars (hence the signage, Million Dollar Hotel). The annex is constructed across the street nine years later.